Presented by Andrew Rubenfeld at the at the regular meeting of the Linnaean Society of New York on January 13, 2015

Yellow-breasted chat just seen in Maintenance. American woodcock by Humming Tombstone. We know exactly where to go to get to these locations quickly. We take the Ramble’s geography for granted just as we take Central Park’s existence as a given. When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux conceived the park in the 1850s, the 14-acre Ramble was designed to be a seemingly natural woodland on whose winding paths one could, well, ramble around big trees, abundant shrubs, tangled undergrowth, and a field here and there.

Don’t take anything for granted is the first axiom of environmentalism.

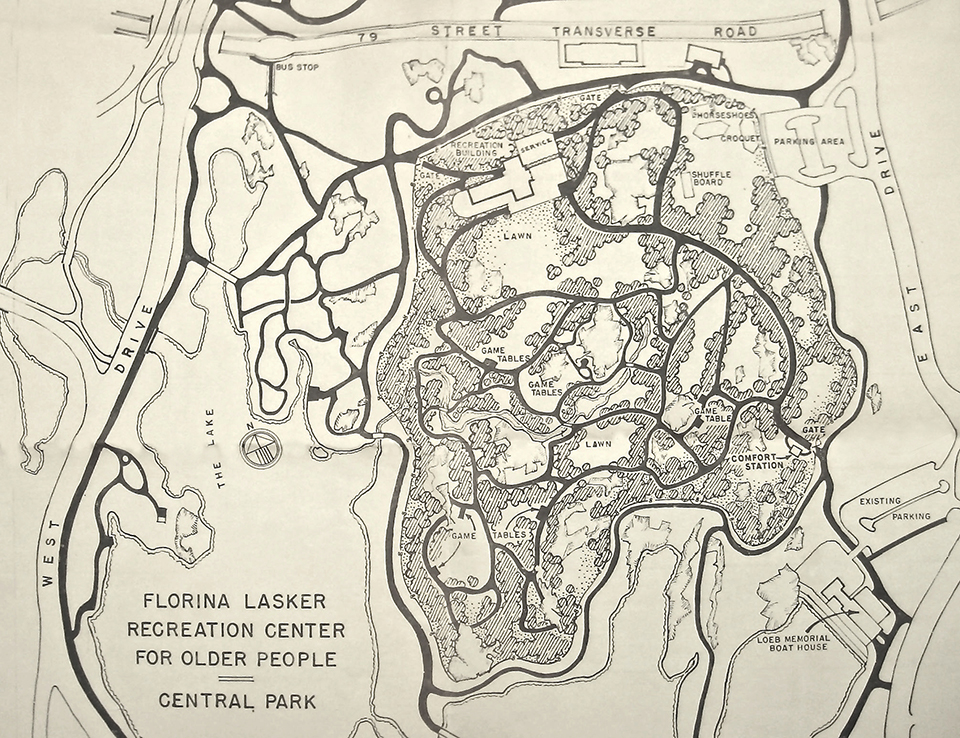

On May 30th, 1955, the New York Times ran the following item: “City’s Senior Citizens to Have a Recreational Center in Central Park.” According to New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses the Ramble was to be converted into a gated indoor and outdoor recreational center for “oldsters” aided by a $250,000 gift from the Lasker Foundation. The city agreed to spend an additional $200,000 to match the grant.

Look closely. Yellow-breasted chat in Maintenance? No, shuffleboard courts! American woodcock by Humming Tombstone? No, game tables! Plus croquet, horseshoes, a large state-of-the-architecture recreation building, and additional comfort stations. Moses said that Parks Department personnel with special understanding of the problems of the older generation would be assigned to the recreational facilities.

Within two weeks the Linnaean Society of New York was leading the opposition. Secretary Lois Hussey drafted a letter to Moses, noting that “the Ramble possesses considerable value as an ornithological study area unique in New York City and also as a wilderness area.” But in a memo to the Linnaean council she observed that “Moses doesn’t care a hoot about birders.” The Society’s conservation committee was opposed to any encroachment on the Ramble on an ornithological basis, but recognized that such opposition might make Moses, who was used to getting his way, “more determined than now to go ahead with the plan.”

In the meantime coordinated letter and telephone efforts by Linnaean members contacted city officials from the mayor’s office to the city council—as well as the media. Linnaean president Irwin Alperin, who offered to meet with Moses, wrote to the New York Times on June 23rd. “Increasing population pressures and the vast expansion of suburban building make preservation of any natural park area within the city a vital necessity,” Alperin wrote. “The choice of site for this commendable project is unfortunate since the Ramble is a unique oasis for migrating birds unparalleled in this region. . . . The fencing . . . of the Ramble . . . will alter and restrict the activities of bird watchers to an alarming extent. It will be impossible to follow flying birds through this fence and certainly the necessity for running back and forth to the exit gates, as birds fly into and out of fenced areas, will make accurate observation a ludicrous performance.” The Times declined to print Alperin’s letter—but had no problem some months later with printing in the Sunday Magazine section a piece by Moses called “The Moses Recipe for Better Parks.”

The battle for the Ramble continued through the summer and fall of 1955. The New Yorker and Cue magazines ran articles. Linnaean conservation chair Kathleen Skelton wrote to Alperin on September 14th: “I think the best thing to do is to keep the publicity going.” George Hallett, a member of the conservation committee, met with Mayor Wagner and Irwin Alperin wrote officially to the mayor on behalf of the Linnaean Society. “The Ramble is justly famous throughout America and in Europe too,” wrote President Alperin, “as a study area for ornithologists and for university and museum students. The continuity of decades of valuable records of observations is threatened by the proposed recreation center.”

By October opposition to the plan had gained momentum. In a New York Times article on October 2nd, entitled “Bird-Lovers Balk at Moses Project,” Richard E. Harrison (also a member of the Linnaean conservation committee) was described as “ridiculing” the idea of making the Ramble a haven for old people, pointing out that the area was one of the hilliest in the park. To get from the proposed new bus stop on the 79th Street transverse road to the proposed recreation building, Harrison observed, would be the equivalent of climbing seven flights of stairs.

Two weeks later the New York Herald Tribune printed a point-by-point critique of the Moses plan by Harrison who emphasized that much of the Moses plan was at odds with the original Olmsted and Vaux vision of the park. Not only bird watchers, but landscape painters, dog walkers, bench sitters, and aimless strollers, he said, would be “bulldozed out of their heritage.” In late November Harrison took Manhattan borough president Hulan Jack on a tour of the Ramble, as reported in the Times.

The following day the Herald Tribune printed an op-ed piece entitled “Bird Watchers and Chess Players.” “One might imagine that the bird watchers and the chess players of this unsettled world have a good deal in common. Both pursue callings that are deliberate, delicate and, in a small way, dramatic. Most citizens hope that they can compose their differences amicably and with a minimum of hard feeling. For the bird watcher and the chess player alike can be a fearsome creature when aroused, and it would be a terrible thing to be caught in a struggle between them.”

By December the plan was all but dead. The environmental opposition was focused and well coordinated. But in the end it came down to money. The New York City Board of Estimate refused to allocate funds. Who would pay for long-term staff? Continuing security and maintenance? Repair of shuffleboard sticks? Lost checkers? Cynicism aside, the city did authorize nearly a quarter of million dollars to restore and protect the Ramble.

In his New York Times Magazine article of January 8, 1956 (mentioned earlier), Robert Moses claimed the last word. Referring to bird-watchers as “nature fanatics,” he added: “Dodo birds with feathers and with pink whiskers have had a field day to the delight of astonished spectators. . . . It’s a dead issue so far as my park boys are concerned. We have other work to do.”

Wrong. Not a “dead issue.” The Ramble and Central Park itself—Jamaica Bay, Sterling Forest, and other areas in our region—will always need our vigilance and support.