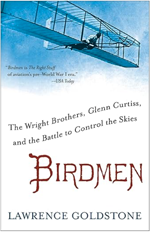

Birdmen: The Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss, and the Battle to Control the Skies, Review by Rosemary MacMillan

Birdmen: The Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss, and the Battle to Control the Skies

Lawrence Goldstone

Ballantine Books, 2024

In 1886 on a hillside in Germany outside Berlin, a wealthy scientist wearing cumbersome wood-framed fabric wings that stretched some 30 feet across checked the direction of the wind and began to run downhill trusting in decades of measurements he had taken that showed him the possibility of flight. His name was Otto Lilienthal and he soared like a bird. Fast forward five years and many trials later with ever more sophisticated wing design and one day, Otto Lilienthal stalled in a thermal and crashed and died. News of his exploits were read by young Wilbur Wright, the president of the Wright Cycle Company in Dayton, Ohio and the germ of aviation took hold.

Thus begins this 386-page book by Lawrence Goldstone, a truly gripping tale of scientific genius, human bravery, determination, and unfortunately, greed. The cast of characters is in the hundreds and features both Americans and Europeans and peripherally, birds, whose seemingly effortless mastery of the air were studied over thousands of hours. As the title indicates, the main characters are the Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss but Mr. Goldstone has a wide brush so throughout the book, the reader is kept informed of the hundreds of young men equally consumed by the flying bug of the Wrights. Given the early 20th century setting, they were all male and probably all Caucasian. The sole female in the story is Katherine Wright, who tended to Wright’s ailing father, and was her brothers’ avid supporter. One cannot help but wonder if she, too, had the same genius as displayed by Wilbur and Orville and what her contribution to flight might have been.

And genius is certainly the correct word to describe the Wrights. Basically, Wilbur designed and Orville built. Prior to their flying addiction they ran a successful bicycle firm which began as a repair shop and soon evolved into a bicycle manufacturing enterprise. The author reminds us of the enormous popularity of the bicycle and the speed of transportation it offered at a time in history when one walked wherever one was going, or was lucky enough to draft a horse for the purpose. We are also reminded that when a particular piece of equipment was needed for some aspect of the job, there was no Amazon to offer all the choices there were in that line. Orville’s only option was to build it, which he did.

Given the popular status of the ‘Wright Brothers’ as inventors of the airplane it might be thought that they were alone in their heroic efforts to master the sky but that is far from the case. As Mr. Goldstone reports, the early 20th century saw countless young men in America and in Europe attempt to get up there with the birds. The French particularly were as keen as the Americans on the idea of flight. Initial efforts by all pioneers consisted of gliding machines. A hilltop was required, wind direction and speed played a huge role, and gravity could be counted on to keep the craft headed back toward the earth. Balance and maneuverability had to be factored in as well. It was all very daunting. Birds, after all, displayed these skills seemingly effortlessly. Maneuverability was achieved by wing design. The thrust they needed for liftoff was supplied by powerful muscles. The only way to mimic that was with a motor. The motor had to be both powerful and lightweight. Orville set to work. Wilbur worked ceaselessly trying to improve wing design. A major competitor of the Wrights was Glenn Curtiss whose expertise was motors. Like the Wrights, he was initially involved in bicycles and was the first to design a motor light enough to be used to power a bicycle – the world’s first motorcycle – which was clocked at a dizzying speed of 30 mph. Also similar to the Wrights, he was taken with the aeroplane bug and soon turned his efforts to producing a motor light enough to allow flight but powerful enough to keep a craft in the air.

The Wrights hailed from Ohio but chose Kitty Hawk, North Carolina for its sandy stretches and prevailing winds of 15 mph to test their invention. They lived in a tent the first season they spent there in 1901 and while there, experimented with gliders. There is an excellent picture of Wilbur lying prone in the center of a bi-winged glider complete with forward elevator which was an airfoil to provide additional lift, as well as a vertical tail as tall as the distance between the wings. Even then the advantage of cambering the wings and making one dihedral and one anhedral had been employed. It was called warping the wings and would later become a point of contention in the Wrights application for patent. One learns, as one reads, an amazing amount of necessary design lingo.

However, all too soon, gliders, with their limits on distance, terrain, and airtime had lost their allure. Even before the turn of the century powered flight had become the goal. The world was gripped by the idea of aviation. There was no shortage in America and in Europe of daring aviators and designers, and equal popularity with the idea of flight on the part of spectators. The ultimate aim of course was to produce airplanes and sell them, and exhibition flying with financial rewards was wildly popular. Audiences numbering in the thousands were happy to pay to observe the miracle of flight. The Wrights held back from almost all exhibitions for fear that their design ideas would be stolen. They were even reluctant to share their accomplishments with the U.S. Army. Early on they tried to secure an agreement without showing either their design or an actual demonstration of what they were offering. Understandably, the Army turned down their proposal.

Enter litigation at which the Wrights, particularly Wilbur, were masters. They finally achieved an injunction against any flights in the United States that did not offer them a royalty. It was largely ignored initially. The French aviators, flying French-designed craft paid no heed nor did Americans, particularly Glenn Curtiss. The argument was that there were so many plane designers that not every feature of every craft could be found to have originated in a Wright design. A perfect case in point was to be seen in a Curtiss plane that won the Scientific American trophy for a flight longer than 25 km. Curtiss’ Golden Flier had ailerons that were obviously superior to the Wright warped wing. He flew in Mineola, New York a distance of 40 km in 19 circuits around a 1 1/3 mile course. The invention of ailerons was copied from the ‘fingers’ of birds which are visible in so many species of large predators and help to direct airflow. It was not an invention so much as mimicking, but birds do not sue.

Though Wilbur Wright’s success in getting an injunction had a dampening effect on all involved in putting on exhibitions -designers, aviators, and investors but it did not stop the impetus of flight. A weeklong meet that took place in Reims, France in 1909 saw Glenn Curtiss entering on the final day with his Reims Racer. The Wrights had refused to participate. Curtiss had gotten to Reims by train with his craft coming along as luggage. He won over Louis Bleriot, perhaps France’s best, in an upset with a speed that was clocked at 6 seconds faster. Curtiss credited his plane’s ailerons with the greater efficiency in turns.

It is amazing to consider that a meet of any distance in the early days of flight required boat and/or train passage. What I find even more astounding is the fragility of early aircraft that could be dismantled and reassembled seemingly without any major construction required.

In 1910 the city of Los Angeles, in a bid for recognition of its growth and perhaps feeling left out in the distant west, invested a sizable sum in prize money to put on an air meet. Curtiss agreed to make an appearance for $10,000 and so did Louis Paulhan, one of France’s best, who was offered $25,000. This in addition to whatever prizes they might win.

As one might expect in a gripping novel, the Wrights injunction was issued the day Paulhan arrived in New York City. He was informed by the Wrights’ lawyer as he disembarked from the Bretagne, and with exemplary Gallic panache, ignored the challenge and boarded a train to Los Angeles. Public relations was with Paulhan who won a distance competition flight distancing over 40 miles, followed by a flight of 20 miles over the Pacific with Mrs. Paulhan as his passenger.

Perhaps fully half of Mr. Goldstone’s book unavoidably deals with big money investors who foresaw, quite accurately as it turned out, the enormous profit to be had from future aeronautic commercial and military travel.

As a birder I notice that a prevailing interest of birders is taxonomy. If you can name it you can put it on your life lists; the friendly competition among birders, often unspoken, seems to be for quantity of species. What Mr. Goldstone has done in his book about the beginning of aviation is to make me aware of all the anatomical, physiological and ecological aspects about whatever little bird that I have finally spotted (usually with the help of other birders). Nor will I ever board another flight again without thinking of all that we owe birds for the marvel of aviation.