The Great Gull Island Project’s Birdathon Weekend Is Coming — May 10-11, 2025!

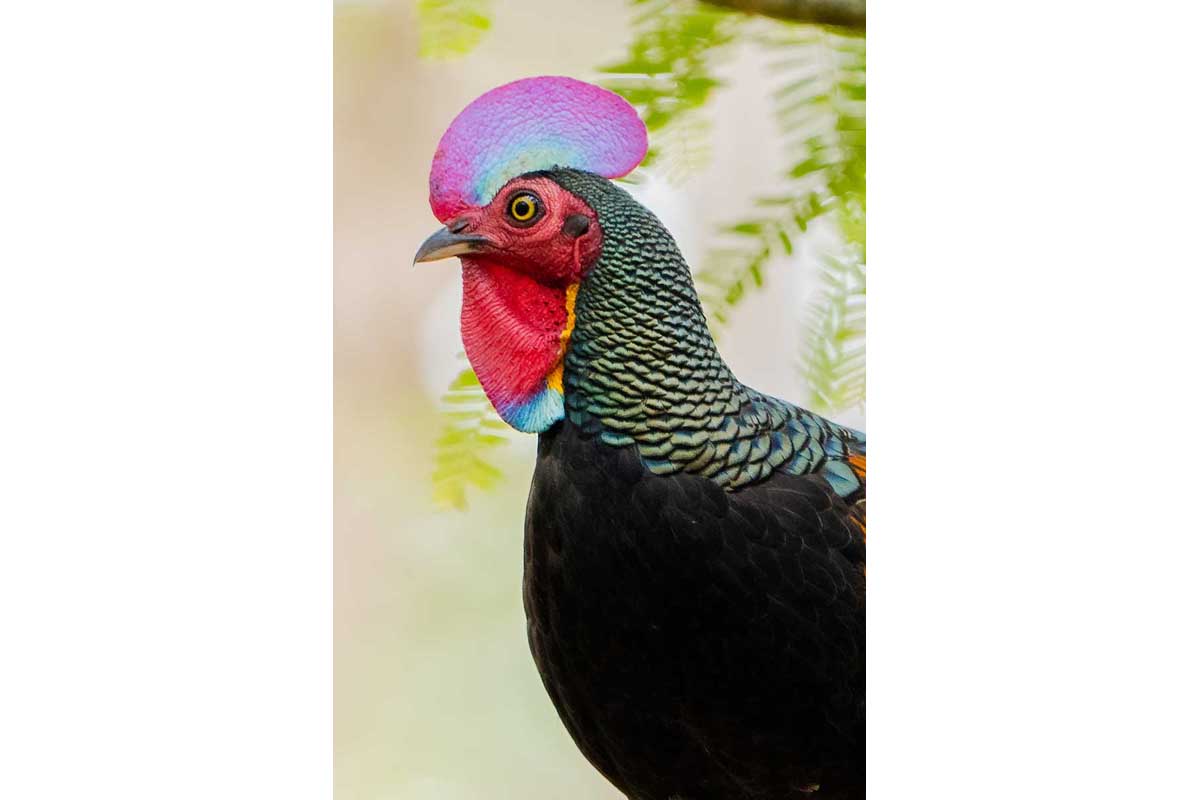

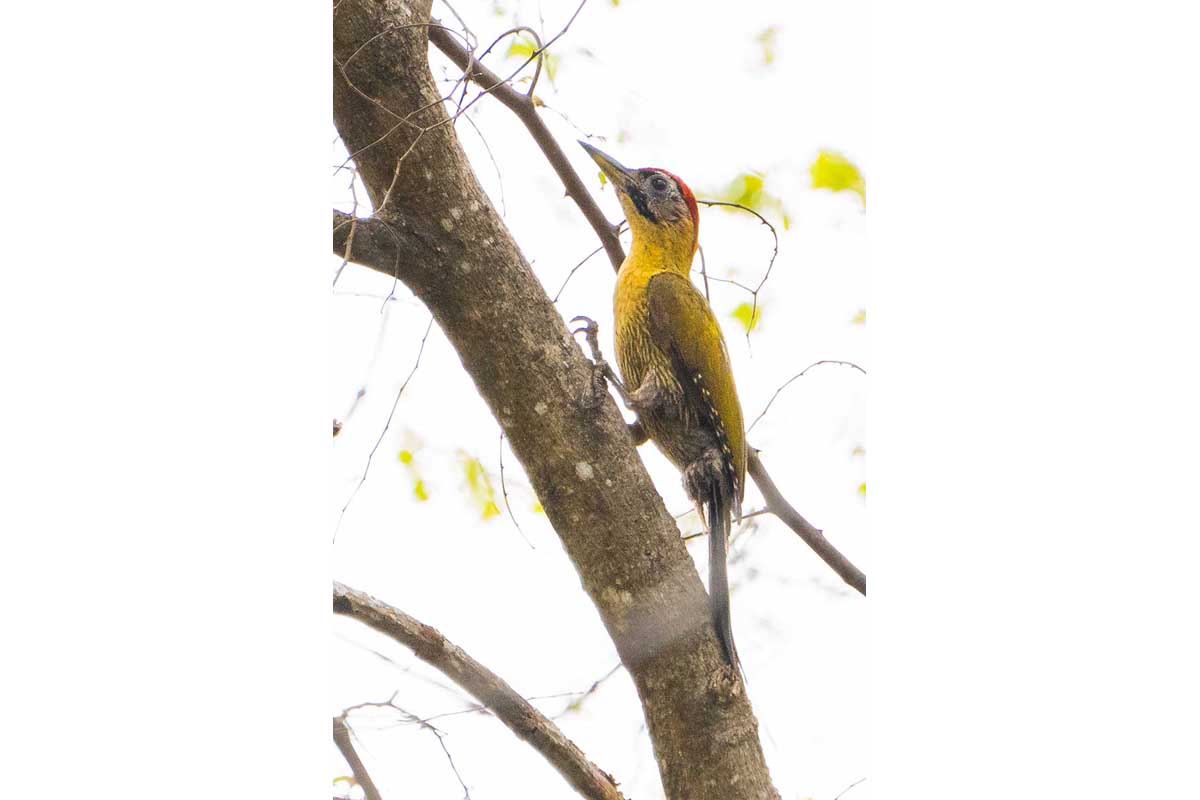

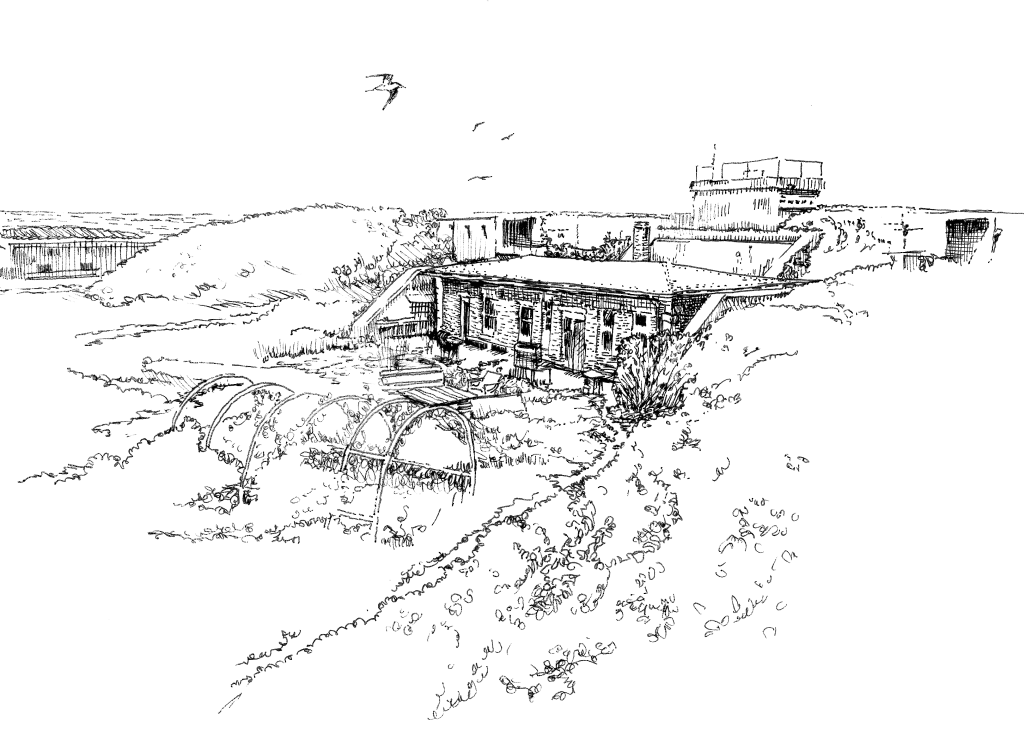

Help support critical research and maintenance of the Common and Roseate Tern colonies on Great Gull Island.

ABOUT THE GREAT GULL ISLAND PROJECT

The Linnaean Society has supported Great Gull Island’s critical tern conservation work since the 1960s. Because of that investment, this tiny island in the Long Island Sound now hosts the Western Hemisphere’s largest nesting colonies of Common Terns and Roseate Terns. Learn More Here

HOW TO PARTICIPATE AS A FUNDRAISER

To ensure the continued success of this work, the Linnaean Society hosts a yearly Birdathon. Birders will form a team or bird solo while identifying as many species as possible over 48 hours. It’s the perfect way to enjoy spring birding while making a difference for critically endangered birds.

STEP ONE: SIGN UP AND DOWNLOAD FORMS (NOW)

- Create a team or decide to bird solo.

- Each participant will then sign up using this form.

STEP TWO: FIND SPONSORS (UP TILL MAY 9TH)

- Ask your friends, family, colleagues, and fellow birders to pledge.

- You may download and print this PDF and ask your sponsors to sign up using this form.

- Or, you can send your sponsors this online registration form to sign up.

- Let them know their contribution is tax-deductible if they pay the AMNH by check and provide their mailing address on the Sponsor Form.

STEP THREE: BIRD YOUR HEART OUT (MAY 10th TO 11th)

- All species counts follow the birding honor system.

- At least two team members must be present to count a species.

STEP FOUR: COLLECTION DONATIONS (MAY 11th to June 15th)

- Share your species totals with your sponsors and tell them their donation total based on their pledge.

- Also share your expected totals with the Birdathon manager team.

- All donations must be received by June 15th, 2025.

- Send your sponsor form to the LSNY Treasurer.

HOW TO SPONSOR OR DONATE

You can sponsor an individual or a team participating in the Birdathon. Please add your information to this Donor Sponsor form. You are welcome to make a per-bird pledge or donate a flat rate for the event.

PAYMENT OPTIONS

- To receive a tax donation form, you must make a check payable to

“GREAT GULL ISLAND PROJECT – AMNH”

- And then mail your check to

Great Gull Island Project

Ornithology—AMNH

200 Central Park West

New York, NY 10024

- Please do not make checks out to the Linnaean Society or your birder.

THANK YOU!

Thank you to all who plan to participate, either as a birder or sponsor! The terns and the hard-working team at Great Gull Island also thank you.