Bali, Indonesia Trip Report – Rahil Patel

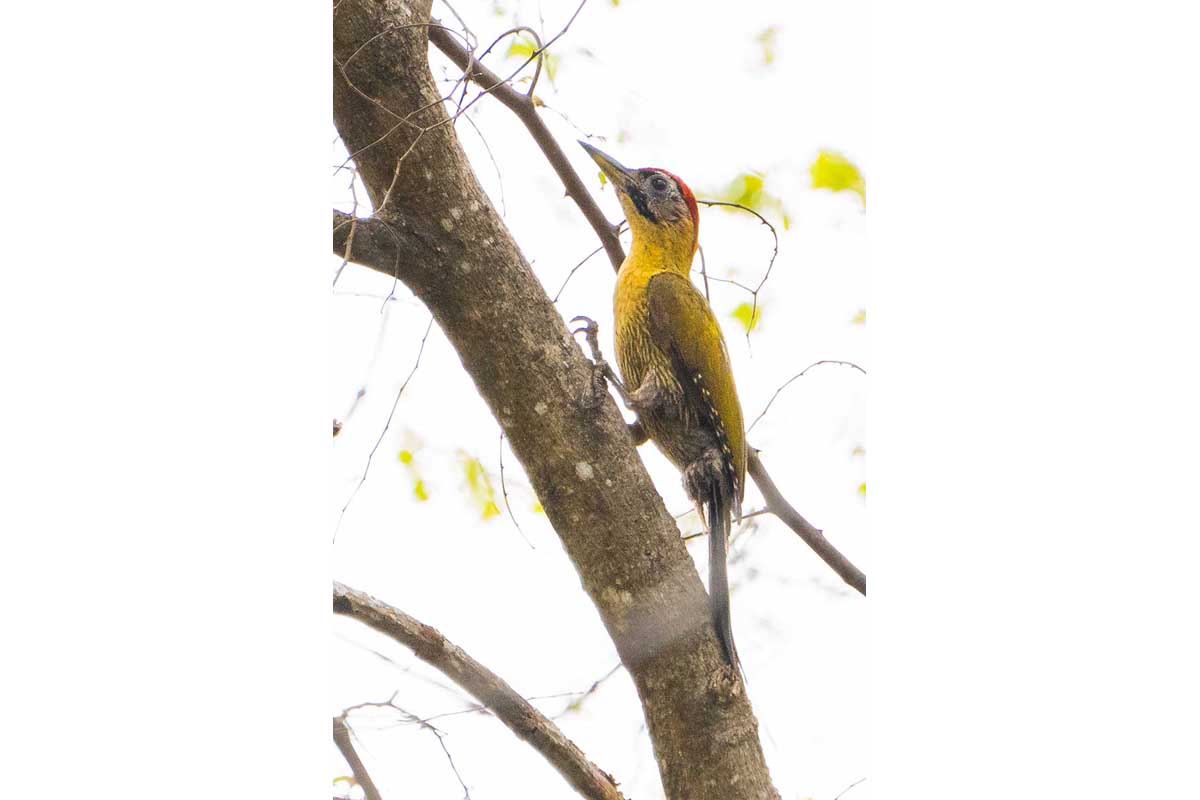

I visited Bali, Indonesia in January 2024 and it was my first time there. Bali has a unique charm for birders due to its endemic species like the critically endangered Bali Myna. The combination of rare bird species and the island’s natural beauty made it a perfect destination. I was most excited to see the Bali Myna and other rare species like the Javan Kingfisher and Javan Banded Pitta.

My itinerary was a mix of family time and birding. I researched key birding locations like Bali Barat National Park and contacted a local birding guide in advance. I made sure to pack all essential birding gear, including binoculars, camera equipment, and field guides. I left two days exclusively for birding while keeping the rest of the trip flexible for exploration. I flew into Bali’s Ngurah Rai International Airport and traveled by car to various parts of the island, including Ubud and Bali Barat National Park. I stayed in Ubud, a cultural hub in the southern part of Bali, at an Airbnb. I primarily used private transportation for longer trips, and local drivers and guides helped me reach remote birding spots.

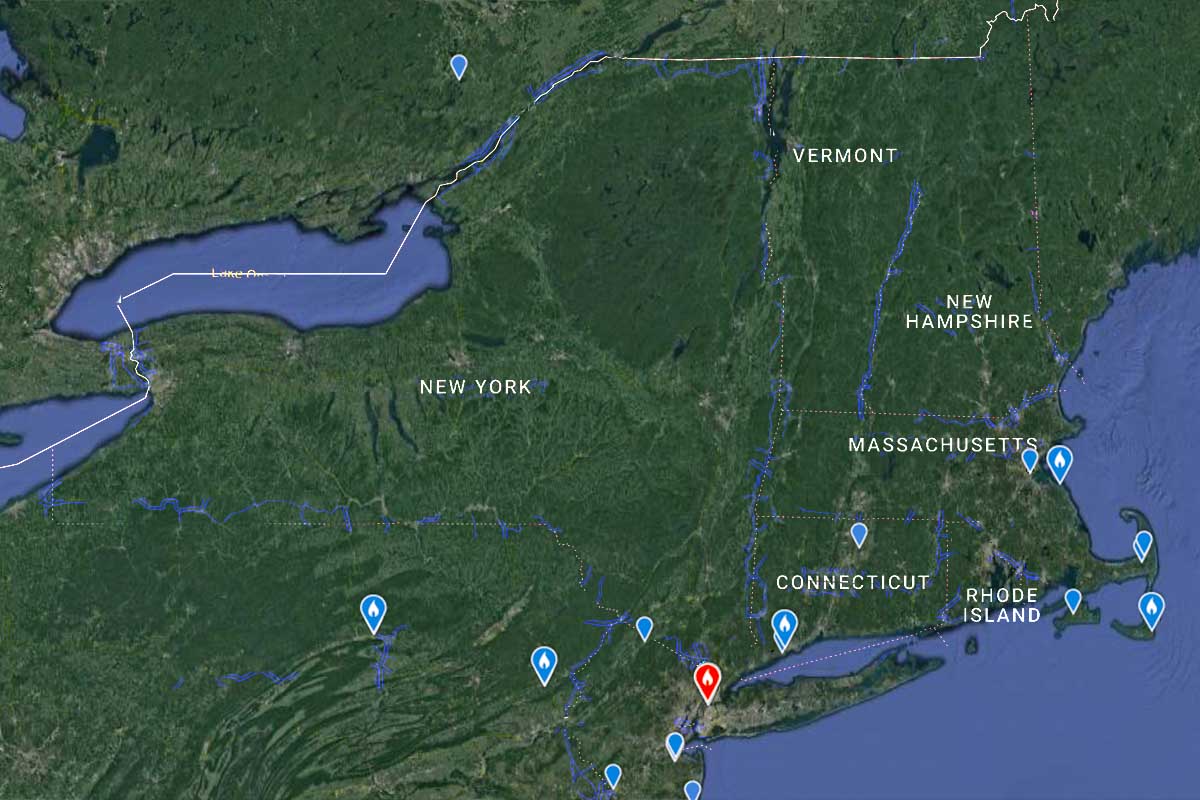

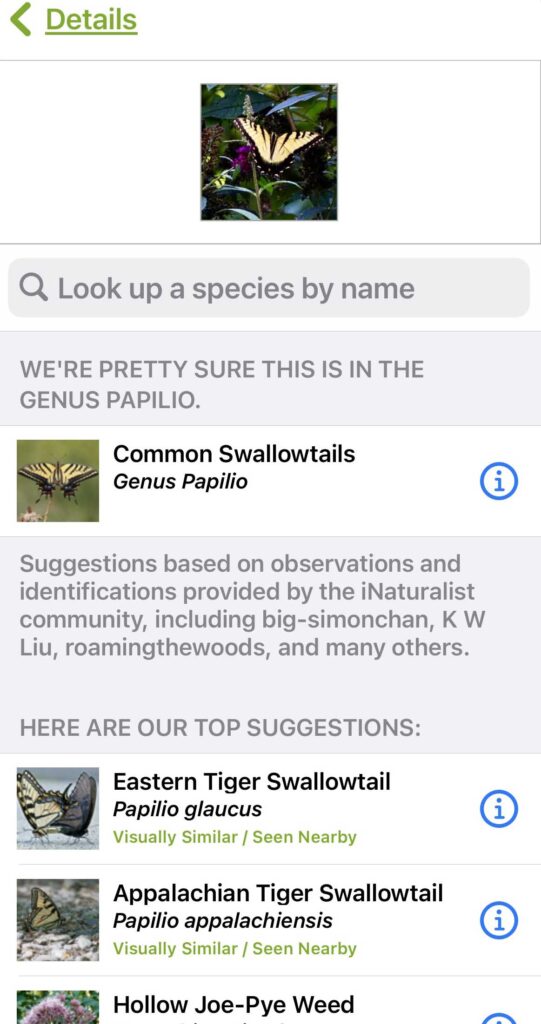

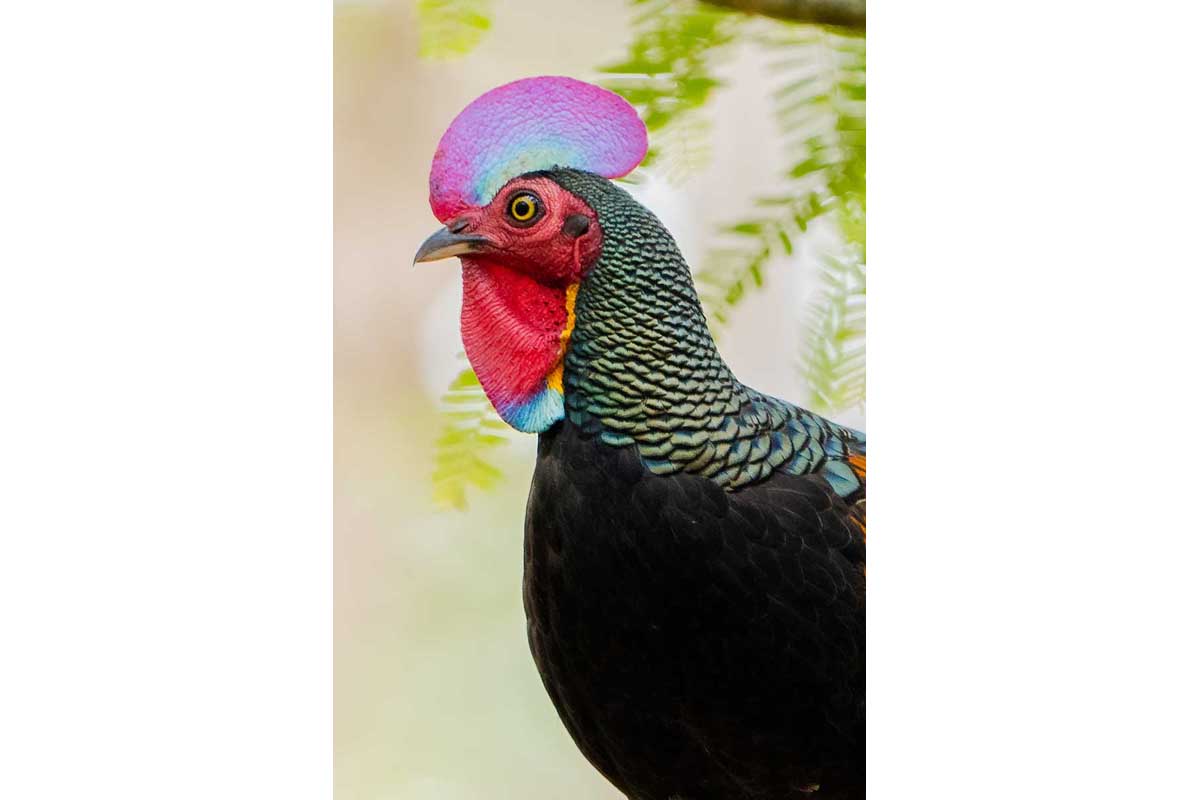

The main birding destination was Bali Barat National Park in the northwest, which is known for its conservation efforts for Bali Myna. I chose this location because it’s a stronghold for several endemic species. I also visited hides and feeding stations set up for birds like the Javan Banded Pitta. Wildlife outside of birds wasn’t my primary focus, but I did encounter various fauna in the park. The natural habitat around Bali Barat National Park was dense and tropical, full of lush vegetation. I used field guides and relied heavily on my birding guide for identifying the birds, particularly the rarer species. The park’s diverse ecosystem made it a fantastic spot for both birding and appreciating Bali’s native flora. I hired a local birding guide, which was essential in finding the more elusive species like the Bali Myna and navigating the bird hides for species like the Javan Banded Pitta.

The first highlight was seeing the Bali Myna – a species once on the verge of extinction – nesting in boxes. I also encountered the Rufous-backed Kingfisher after a long wait at a hide meant for the Javan Banded Pitta. The next day, I successfully spotted the Javan Kingfisher. However, I missed the Sunda Scops Owl while birding, though I had a surprising second chance at our Airbnb, where my parents spotted one. I managed to see it, but I couldn’t take great photos because I lacked a torch. Lastly, a rare find was the Red-chested Flowerpecker, spotted at a different resort, which was a great bonus as it had only been seen twice on the island. The biggest surprise was the owl encounter at our Airbnb! After missing the Sunda Scops Owl in the field, I didn’t expect to find one just outside our accommodation. Sadly, the moment was a bit frustrating as I didn’t have a torch, and by the time I retrieved one, the owl had flown off, leaving me with grainy images.

Given a chance, I would absolutely go back! Bali’s diversity of species and habitats makes it a must-visit for any birder. I would return during the dry season for potentially better conditions and would be more prepared for night birding with a good flashlight. Also, I’d love to revisit Bali Barat National Park and explore even more hidden birding spots. Bali offers a great balance between wildlife and culture. Even if you’re not birding, the island’s landscapes and rich cultural experiences make it a fantastic destination. If I had more time, I would have loved to explore the nearby islands for even more endemic species.

Advice for someone looking to do this trip:

Best time to go: Dry season (April to October) is ideal for birding, though I visited in January and still had good sightings.

Essentials: Binoculars, camera with a good zoom, field guides, a torch for night birding, and insect repellent.

What to wear: Lightweight, moisture-wicking clothing is ideal for the heat and humidity, along with sturdy walking shoes for birding treks.

Sights not to miss: Bali Barat National Park for birding, especially if you want to see the Bali Myna.

Services: Hire a local birding guide – they know the spots where rare birds frequent and make the experience much smoother.

Food: Balinese cuisine is delicious and varied, with a lot of fresh seafood and rice dishes. Ubud, in particular, has many excellent restaurants with options for all diets.

Local customs: Bali is a predominantly Hindu island, so it’s essential to dress modestly when visiting temples or rural areas.

Author: Rahil, Patel; Avid Birder, Linnaean Member