Presented by Patrick Baglee at the regular meeting of the Linnaean Society of New York on January 13, 2015

When I was around 8 years of age, one of my Mom’s chief ambitions for me was that I became archivist of the Royal family’s collection at Windsor Castle. Or Balmoral. In fact to be an archivist anywhere with a Royal connection would have been fine.

Much to her chagrin, I showed more of an affinity with my father’s profession. He was a compositor, and one of his books (‘Printing Design and Layout’, by Vincent Steer) held me in such rapt fascination that the idea of life as a curator paled.

And yet, the essence of an archivist’s life must have remained dormant because when I was invited by the Linnaean Society’s vice president Andrew Rubenfeld to visit the Society’s archive at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), I accepted without hesitation.

In the early summer of 2014, Andrew, fellow Linnaeaen Society member Anders Peltomaa and I arrived at the archive at the Ornithology Department of the AMNH to be greeted by our host Paul Sweet, Collections Manager, Vertebrate Zoology, Ornithology. Once we had signed in he led us to a rather unprepossessing grey filing cabinet tucked away in the office directly opposite his own.

With other collection cabinets looming over it there is just enough room for one person to stand before the archive and reach inside to take out material. A solid built wooden desk in the adjacent room makes for a convenient place to lay out papers. Taking my turn in the narrow gap in front of the cabinet, I carefully looked it over from top to bottom.

Hard-bound books, two boxes containing reel-to-reel tapes, loosely packed office files and an old Amazon.com box were the first things to catch my eye. A number of royal blue hard-bound copies of the Proceedings of the Society were at eye level. Alongside them were older, gilt-edged volumes that contained page after page of diligent copperplate hand recording the payment of Society dues.

Most impressive were around a dozen grey archival boxes, each neatly annotated, covering a wealth of Society correspondence, minutes and ephemera (all thanks — as I would later discover — to the hard work of Gil Schrank). But then something else caught my eye in the shadows at the back of the cabinet.

Tucked behind several volumes of Society proceedings, all but hidden from view, was a single manilla envelope. Alongside it were stacked 10 or so hard-bound books of different types, leaning to the left. Beside them was a cardboard folder tied with a pink ribbon. I reached in and lifted out the manilla envelope.

Inside were 15 notebooks, of varying shapes and sizes. Some were plain black, some wire bound and at the back was an A6 ring bound notebook with loose-leaf pages. Lifting them out, the first book (which fit snugly in my palm) was labelled ‘Dr Edmund R P Janvrin’s field notes of birds New York and Vicinity 1915-1916’. These books appeared to contain notes from the field. The larger notebooks ran from 1920 to 1968 and contained more comprehensive field trip accounts. The separate cardboard folder had a concertina-type arrangement to store its contents and held loose sheets covering all of Dr Janvrin’s observations of water birds in North America.

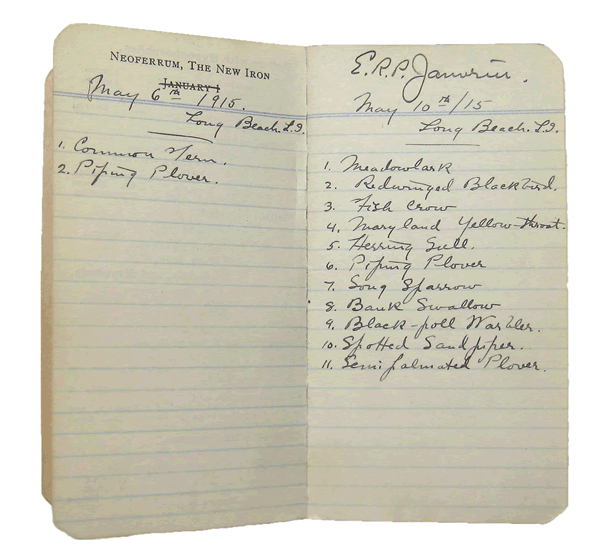

I took a close look at the first of the field notebooks. It opens on May 6th 1915 with Dr Janvrin’s sightings of Common Tern and Piping Plover at Long Beach. Each species is numbered in order of observation; four days later the species count rises to 11. The notebooks — at first glance — were fascinating. But I realised there was one thing I did not have a good grasp of; as a relatively recent member of the Society, and without intimate knowledge of New York ornithological circles, I was unaware of Dr Janvrin’s role and impact on the ornithological history of the city and the State.

Taking the dates of his notebooks as reference, I consulted an early volume of the Proceedings and discovered (much to my embarrassment) that Dr Janvrin — as well as being a highly respected and very busy man of medicine — had performed practically all the significant roles within the Society. He was elected a member in 1918, served as Secretary from 1920-22, as Vice president from 1924-26, as President from 1926-27 and as Treasurer from 1931-35. He was re-elected to serve a second term as Vice-President from 1939–41, and made a Fellow in 1956 on the recommendation of Eugene Eisenmann.

All told, he was a member of the organisation for 55 years. In his stint as President, he dealt with both Society and regional ornithological matters. In the winter of 1926 he wrote a letter, published in the New York Times, complaining about the wholesale slaughter of Snowy Owl during a major influx of the species on Long Island.

His commitment as a field ornithologist also placed him in the pantheon of New York State birders. His observations were regularly cited in published works (Ludlow Griscom’s ‘Birds of the New York City Region’, published in 1923 being one example), and his familiarity with the birds and habitats of Long Beach made him an acknowledged expert on the area and its bird and wildlife (though his modest character would no doubt mean he would never outwardly claim the same).

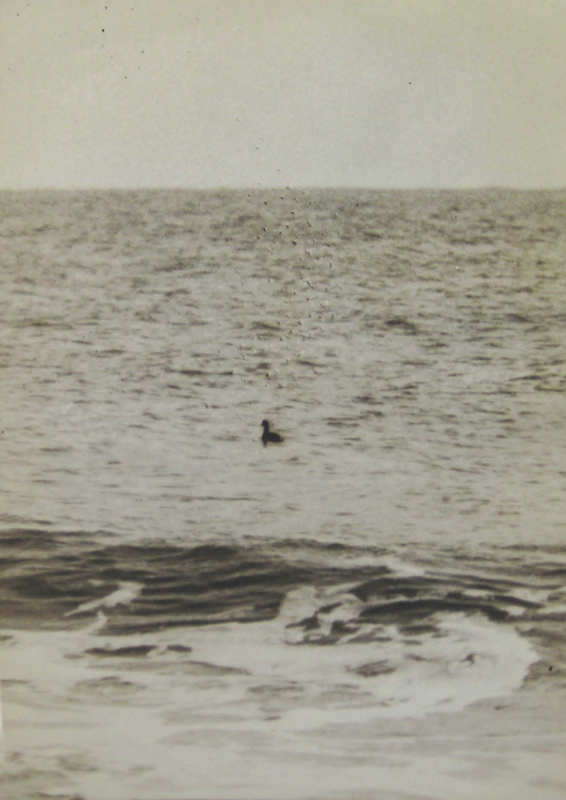

His tireless days in the field would lead him to make some exciting discoveries, most notably an Eared Grebe — at that time the first record of the species for the East Coast. A female King Eider was another prized sighting, though the supporting photograph of the bird serves only to indicate just how far photographic and optical equipment has come since the middle of the last century.

Leafing through the larger more formal notebooks, I found other items of interest that Dr Janvrin had been keen to retain alongside his field notes. Press cuttings about specific events of ornithological interest — like the discovery of Harlequins at Point Lookout, a wreck of Dovekie in the city and the appearance of a Glossy Ibis in Van Cortlandt Park — are glued in at the appropriate date. His own photos of sites visited are also incorporated.

More personal still are dozens of pictures of himself and his family out birding in all seasons at Long Beach and elsewhere. There are Christmas cards from his daughters (including one of a very fetching Cedar Waxwing by Don Eckleberry). There’s even a picture of a new Ford from the 1940s. At the back of each of the larger notebooks is a cross referenced list of the places that Dr Janvrin had visited during that book’s period.

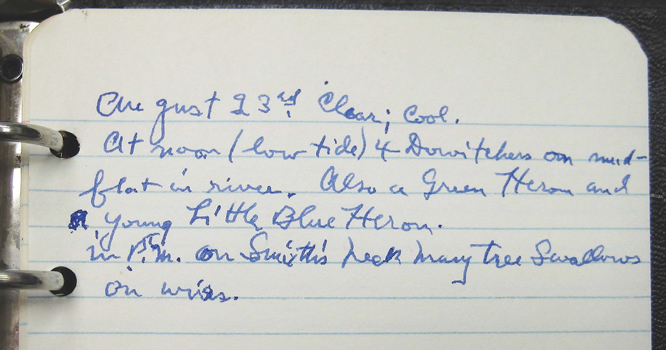

The final notebook entry, dated August 23rd 1972, indicates that he was still an active field ornithologist well into his 80s and anecdotal remarks from other parts of the archive show he was still a regular attendee at Society meetings at the same time. When he passed away, at his summer home in Connecticut in 1973, an announcement was made to members of the Society during the September of that year.

In preparing to give a short talk on the notebooks of Dr Janvrin to the Society in January 2015, I was fortunate enough — thanks to the help of Helen Hays — to make contact with Mary, Dr Janvrin’s surviving daughter. In a brief conversation, I was able to outline the topics I would cover in the talk, and she was both thrilled that her father’s devotion to natural history would be spoken about, and happy to support my efforts. She spoke warmly of the days the family would spend out in the field; of generous picnics, cold days on the coast and the shared love and respect for wildlife that she and her sister Natalie carried forward.

The opportunity to dip into the archive was a privilege. I was able to piece together a unique view of a significant figure in New York’s ornithological history, and I was able to better understand the social fabric of New York ornithology (and the importance of the Linnaean Society as one of its focalpoints). Most importantly, it gave me a glimpse of the potential riches that lie within the Society’s archive. I barely scratched the surface and yet even this cursory examination revealed a wealth of fascinating connections.

I can only begin to imagine what others might be inspired to unearth from within the archive’s modest environs.

Acknowledgements: with grateful thanks to Andrew Rubenfeld for the original invitation to visit the archive and for the opportunity to prepare a short lecture, delivered at the member’s meeting on January 13th and on which these notes are based; to Thomas Trombone, Lydia Geratano and Paul Sweet for their help in providing subsequent access to the archive, and to Helen Hays for her help and assistance. Finally, to Mary Janvrin, my sincere thanks for her support and encouragement.