Mallards and Wood Ducks are the most common breeding ducks in New Jersey. While both species breed in fresh water habitats throughout the state, their life styles are quite different. Mallards are hardy, gregarious, ground nesting ducks that are present in New Jersey throughout the year. The familiar green headed drakes and drab hens are common in ponds and parks where they eagerly seek handouts. The crested drake Wood Duck in breeding plumage (below) is a strikingly beautiful multi-colored bird. The hen (next page) has a distinctive large white eye patch. Wood Ducks in spring can occasionally be seen perching high above on tree braches as they seek a nesting cavity.

Wood Ducks are shy and distrusting cavity nesters that prefer wooded wetlands and mostly migrate to the southern half of the United States for the winter. Wood Ducks are small and weigh about half as much as Mallards. Both hen Mallards and Wood Ducks begin laying large clutches of about ten eggs in early spring. Only a single clutch is raised in New Jersey. If the first clutch fails, the ducks may renest. The hen lays an egg a day until the clutch is complete. The eggs are then brooded for about four weeks until the fully feathered precocial (capable of feeding themselves) chicks hatch. The hens are single moms that select the nest site, brood the clutch, coax their new hatchlings out of their nest and shepherd their young until they are able to fly in about two months. The drake’s primary mission is to woo the hen and fertilize the eggs.

The New Jersey Wood Duck population was decimated and nearly extirpated in the early twentieth century due to habitat loss and unregulated market hunting (Walsh et al., 1999). The harvesting of mature hardwood forests reduced available nesting cavities. The Migratory Bird Treaty of 1918 regulated hunting and the introduction of artificial nest boxes and enabled the remnant Wood Duck population to rebound to the current robust levels.

Every spring abandoned ducklings are found by concerned individuals that want to get them out of harm’s way. Usually the ducklings’ mother has been killed or is no where to be found. Orphaned ducklings can come from unexpected places such as roads, garages, storm sewers and even felled trees in the case of Wood Ducks. One duckling was recovered by a fisherman from a snake that had grabbed the last duckling swimming in a line. The fisherman hit the snake over the head and was able to retrieve the duckling. However, the mother duck and rest of her clutch had disappeared in the meantime.

Abandoned ducklings should be transferred to a rehabilitation center as soon as practical to increase their chances of being successfully raised and eventually released into the wild. It is unlawful to attempt raising a wild bird without a permit. Most ducklings die because they get cold. The most important thing for someone who finds an orphaned duckling is to keep it warm and dry until it can be transferred to a rehabilitation center.

As would be expected, orphaned duck- lings in New Jersey are primarily Mallards and Wood Ducks since they are the most common breeders. Mallard chicks respond well to human parenting. They have a high survival rate if provided with the basics of food, water, and a safe place. They readily become acclimated to the presence of humans

Wood Ducks are not susceptible to taming. They retain the shy and secretive characteristics of their breed. They avoid human interactions. Orphaned Wood Duck chicks are known by rehabilitation centers to be difficult to raise. Their mortality rates can be excessive. The second author is a former State and Federal permitted duck rehabilitator who now serves as an off–premise rehabilitator of Wood Ducks for the Raptor Trust. She uses her residence to provide the privacy required to successfully raise Wood Duck chicks. Judy handles the dozens of ducklings of this species that are annually received by the Raptor Trust. The first ducklings are usually received in late April. Ducklings from later clutches arrive until early June.

The key to raising young Wood Ducks is to get them to settle down and begin eating during their first few days in captivity. They should be given as much privacy as practical during their entire captivity. Judy houses newly hatched ducklings inside her garage in a heated box that is approximately two feet by three feet wide and eighteen inches tall. The box has a wire cover to prevent ducklings from jumping out. In the wild, the hen Wood Duck calls her young out of their nest box within 24 hours of hatching. Afterwards the ducklings evidently don’t want to go back into a box. The box in Judy’s garage is heated with a sixty watt yellow bug light. The bottom of the box is covered with newspaper and then a layer of paper towels to create a spongy surface. This enables the ducklings to see food that moves as the ducklings walk on the paper towels. This movement entices the ducklings to begin eating. A shallow one inch deep pan with water is at one end of the box. The end of the box beneath the light is made higher with folded towels. Ducklings like to get up as high as they can. A food bowl is put in the center of the box. Clumps of grass and dirt are placed on the floor to create a more natural environment. Duckweed is placed in the water dish and on the walls.

When new ducklings are received, they are put in the water. They may drink but most likely will run to other end of box to get as far away as possible. At least they learn where the water is located. When they are all in the box, it is covered with a towel with a small opening for a peek hole. The ducklings are left alone for the first six hours. If they stop jumping and are resting under the light, they are sprinkled with ground up hi-protein dog food bits. It looks and moves like bugs and may trigger feeding. After cleaning the box, food is put on the floor and meal worms in the feeding bowl. The box is cleaned twice a day. The hi-protein dog food is removed from feed after four days and meal worms are discontinued after ten days. Commercial duck food is the primary diet for the rest of their captivity.

After two weeks the ducklings are transferred to a larger open box inside the garage. Depending on the weather at 3-4 weeks they are transferred to large outside wire cages that contain vegetation and a water pond. The Wood Ducks are amazingly adept at hiding in the grassy area of their pens. Food and fresh water are replenished once a day. The ducks are released into the wild once their down begins to be replaced with feathers. The ducks are released in areas in the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge that are known to harbor Wood Ducks. The existing Wood Duck population will hopefully help the assimilation of the captive raised ducks into the wild.

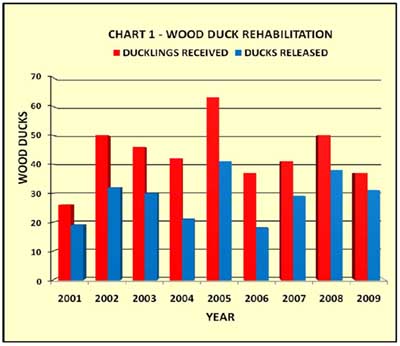

Chart 1 presents the Wood Duckling raising data for the last nine years. Nearly two-thirds of the orphan ducklings lived to be released during this period. Most fatalities occur in the first few days after arrival. Ducklings usually live at least a day after being placed in their new box home. If they survive for three days, their chances of being raised and released are very good. A lone Wood Duckling is particularly difficult to raise. A lone Wood Duck could be put in with mallard ducklings of a similar size. However, a small duckling should never be put into a box with larger ducklings.

Keeping orphaned Wood Duck young warm and dry and getting them to a rehabilitation location as soon as practical is a key in preventing the ducklings from becoming too weak and traumatized to be successfully raised.

Literature Cited

Walsh, J., V. Elia, R. Kane, and T. Halliwell. 1999. Birds of New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society.